Were you to go back in time to July 2021 and ask a political observer what federal indictment the person might expect Donald Trump to face in two years’ time, there would have been a consensus. Not that he would face charges related to his retention of classified documents, as he does; at that point, about the only people focused on that issue were representatives of the National Archives.

Instead, you’d have heard predictions centered on the 2020 election and Trump’s efforts to retain power despite his election loss, including by calling for people to protest in Washington on Jan. 6, 2021. It was this effort that seemed most obviously likely to have violated federal law.

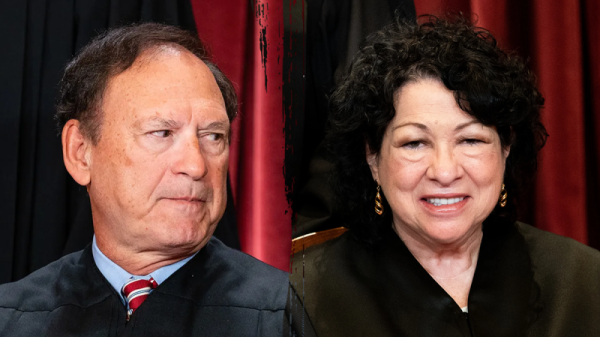

As months passed, that expectation hasn’t diminished much. In evaluating whether a Trump attorney’s communications with his client should be turned over to the House select committee investigating the Capitol riot, a federal judge outlined several federal laws that Trump probably violated, including an effort to obstruct an official proceeding and conspiracy to defraud the United States. Last year, media attention on the illegitimate slates of electors submitted by Trump’s campaign spurred a new look at that December 2020 effort.

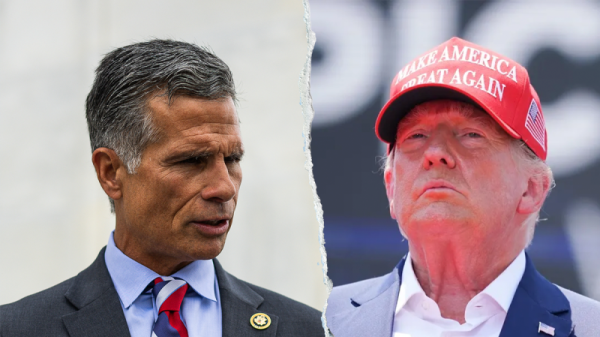

For much of the first two years of President Biden’s term, though, the Justice Department hesitated on an expansive probe into Trump’s actions. When Trump announced his candidacy for the 2024 Republican presidential nomination, Attorney General Merrick Garland appointed Jack Smith to serve as special counsel overseeing a slate of investigations into Trump’s actions. And, in short order, Smith began issuing subpoenas and accepting grand-jury testimony.

One of the threads Smith was considering, the one centered in Florida, resulted in last month’s indictment of Trump related to his retention of documents. At the same time, the broader probe considering Trump’s response to the 2020 election — in reality, a number of separate lines of investigation — also picked up its pace.

To get a sense of where things stand, we have compiled the following list of individuals subpoenaed for information or who have offered testimony or information to Smith’s investigators. The picture that emerges is of a wide-ranging probe, but one with some obvious holes.

Garland appointed Smith on Nov. 18. Smith had issued subpoenas to elections officials in three states that were targeted by Trump and his allies after the election: Arizona, Michigan and Wisconsin. A subpoena obtained by NBC News indicates that investigators sought any communications between the officials and more than a dozen people working with or in alliance with Trump’s reelection campaign as well as the campaign itself.

By December, a grand jury in Washington heard testimony from people close to Trump, including former White House counsel Pat Cipollone and his deputy Pat Philbin.

In January, the grand jury heard testimony from Ken Cuccinelli, who’d worked in the Department of Homeland Security under Trump, and John McEntee, an adviser to Trump who was described by ABC News’s Jonathan Karl as the staffer who “made the disastrous last weeks of the Trump presidency possible.”

In February, a number of state legislators from Arizona received subpoenas. One, state House Speaker Ben Toma, told the Arizona Republic that he wasn’t “certain why he received a subpoena, although as the number two leader in the House of Representatives in 2021, he was involved in conversations about what actions, if any, the Legislature could take regarding the results of the presidential election.”

This also may have been the point at which the FBI interviewed former Arizona House speaker Rusty Bowers, whose testimony before the House select committee became a media sensation.

That same month, a number of other people close to Trump also received subpoenas. Among them were Ivanka Trump and her husband, Jared Kushner, former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and former national security adviser Robert O’Brien.

In April, a number of high-profile witnesses offered testimony before the grand jury. One was former vice president Mike Pence, whose efforts to block his February subpoena were rejected. When he offered his testimony, Smith was in the room.

Three other Trump allies/staffers also appeared before the grand jury in April. One was Stephen Miller, Trump’s longtime speechwriter, who was involved in crafting his speech for the Jan. 6 rally. Another was John Ratcliffe, who served as director of national intelligence. Trump’s longtime aide and legal adviser Boris Epshteyn was interviewed over multiple days.

In May, Smith subpoenaed the office of the Arizona secretary of state. At some point in the same period, he also received testimony from legislators in the state, although it’s not clear when.

The special counsel’s probe also looped in more high-profile figures. Former Trump adviser Stephen K. Bannon was subpoenaed, and Trump’s social media director Dan Scavino appeared before the grand jury. So did Nick Luna, another close aide of Trump’s.

By June, the testimony was coming fast and furious. Former House speaker Newt Gingrich, who’d advised Trump in the post-election period, appeared before the grand jury. So did several members of the Secret Service, after being subpoenaed in April. Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, subpoenaed in December, was interviewed by Smith’s office last month. So was former Trump White House aide Alyssa Farah Griffin.

The probe also began more obviously to focus on other lawyers who had aided Trump’s post-election efforts. Rudy Giuliani, probably the best-known of the group, sat with Smith’s investigators. This apparently followed a proffer agreement in which Giuliani might agree to cooperate with investigators. Mike Roman, a Trump campaign staffer, reportedly met with investigators under the same conditions.

One of the most notable developments in June was that several of those who served as illegitimate electors on Trump’s behalf also offered testimony before the grand jury.

“At least half a dozen witnesses have testified before the federal grand jury in Washington over four days in the past two weeks,” CNN reported June 23, “with many of the sessions focused on the fake electors’ plot orchestrated by attorneys assisting the Trump campaign in 2020.”

It is obviously not clear what these witnesses were asked about, although reporting does suggest a number of directions Smith’s probe is taking. There’s the Capitol riot itself, of course, as well as efforts to pressure legislators to reject presidential election results in states after November 2020. There’s the fake-electors scheme and, according to reporting, consideration of Trump’s efforts to fundraise off his challenges to the election.

It also is notable who isn’t understood to have been contacted by Smith’s office yet in regard to the post-election probe. (This excludes Trump allies, like campaign adviser Susie Wiles, who offered testimony related to the Florida documents probe.) Foremost among them is former Arizona governor Doug Ducey, who The Washington Post reported faced repeated pressure from Trump to overturn his state’s results in the presidential election. It also is not known whether Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp — another Republican governor of a state that flipped to Biden — has been contacted by the special counsel.

We also don’t know whether former Meadows aide Cassidy Hutchinson — who offered explosive testimony before the House select committee — has talked to Smith’s investigators. That’s also true of former White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany and Trump’s longtime adviser Roger Stone. Trump’s legal adviser John Eastman isn’t known to have been contacted, but that may be a function of his being a possible target of criminal prosecution.

Since the special counsel probe is conducted under seal, it is possible that these and other individuals have in fact spoken with investigators. Again, though, the picture is clear: The probe is both broad and deep. It is impossible to know whether charges will result and when, but if they do not, it certainly will not be not for lack of investigating.